Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

Lot 35

[Americana] [Washington, George, and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette] The Destruction of the Bastille

Sale 2101 - Books and Manuscripts

Sep 10, 2024

10:00AM ET

Live / Philadelphia

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$500,000 -

800,000

Price Realized

$1,996,000

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

[Americana] [Washington, George, and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette] Cathala, Étienne-Louis-Denis. The Destruction of the Bastille

A Tribute to the Patriarch of Liberty: The Marquis de Lafayette’s Personal Gift to President George Washington of a Drawing of the Demolished Bastille

"Give me leave, My dear General to present you with a picture of the Bastille, just as it looked a few days after I Had ordered its demolition...it is a tribute Which I owe as A Son to My Adoptive father, as an aid de Camp to My General, as a Missionary of liberty to its patriarch." (Lafayette to Washington, March 17, 1790)

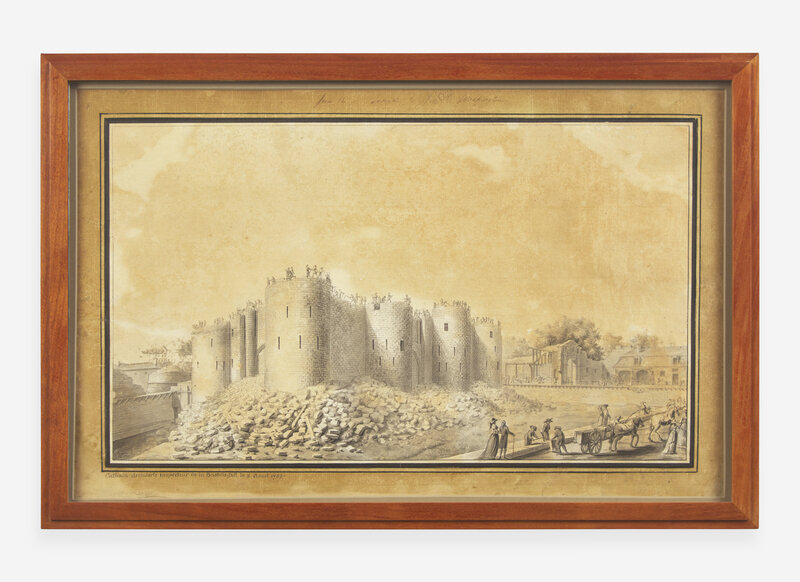

Paris, August 8, 1789. Ink and ink wash on laid paper, mounted to secondary laid paper sheet; triple black ruled ink border (possibly added at a later date). 11 3/4 x 18 1/2 in. (image), 13 1/8 x 20 3/4 in. (sheet). Presented by the Marquis de Lafayette to President George Washington and inscribed by Lafayette at top: "From the M. de Lafayette to General Washington"; inscribed at bottom by the artist, Étienne-Louis-Denis Cathala: "Cathala Architecte Inspecteur de la Bastille fait le 8 Aoust 1789". In modern frame, 15 x 22 1/2 in. Sheet toned; scattered surface wear; abrasions in top corners. Professionally cleaned and restored; black border with some in-painting; small areas of in-painting in corners and at top and bottom.

A remarkable drawing attesting to the historic friendship between George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette, and the confluence of the American and French Revolutions.

On July 14, 1789, the people of Paris stormed the Bastille prison, igniting a full-blown revolution in France. The very next day, the Marquis de Lafayette, hero of the American Revolution and then one of the most powerful figures in France, was appointed leader of the newly mobilized Paris militia. The city’s municipal government was unanimous in its choice of Lafayette to lead this citizen army. He was the ideal candidate, given his well-known military experience in America which was instrumental in the United States' victory over Great Britain, and because of his political influence in France that contributed to the rise of the French Revolution.

The militia was formed on July 13, only two days prior to his appointment, and it was its members, along with the citizens of Paris, who stormed the prison-fortress in search of weapons. Charged with upholding law and order in a city seething with anger, frustration, and hunger, Lafayette's leadership of this militia was shaped by his experience while serving under General George Washington in America. Like his mentor, Lafayette sought to wield his immense power in the service of liberty, and he demonstrated this by subordinating his command to civic control, subjected his appointment to election, refused compensation, and declined opportunities that would have allowed him to usurp complete power. In the process, he transformed the militia into a well-disciplined volunteer army. He renamed it the Garde Nationale, or National Guard, and through his actions garnered the affection of the Paris populace. To inspire confidence among the public, Lafayette designed an emblem for its troops to wear, a tri-color cockade comprised of blue, white, and red: a combination of the red and blue colors of Paris and the white of the House of Bourbon—a lasting symbol that is now the tricolor of the French national flag.

Soon after Parisians conquered the Bastille, the process of its demolition began. As early as the night of July 14, architect Pierre-Francois Palloy and his crew began to raze the prison. Aware that its continued presence inflamed public sentiment, on July 16 the municipal government of Paris authorized its complete destruction, and tasked Lafayette with seeing to its orderly demolition. Lafayette signed an order authorizing Palloy's work, and government officials were then sent throughout Paris to proclaim in Lafayette's name the fortress's imminent destruction (1). Less than four weeks later, on August 8, Étienne-Louis-Denis Cathala, one of the site's six demolition inspectors, created this drawing for Lafayette. Once an imposing fortress and symbol of the French monarchy’s tyrannical oppression, here Cathala shows the “citadel of arbitrary power” (as Lafayette called it), in complete ruin at the hands of the French citizenry (2).

On March 17, 1790, after eight months of tirelessly meeting the many-sided demands of his new position, Lafayette wrote to Washington to inform him of the Revolution’s unfolding events. Lafayette was then at the height of his power, and he was optimistic about the Revolution’s direction, which he was steering in a moderate course toward a constitutional monarchy. The National Assembly was assembling its first Constitution (whose preamble, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, was first drafted by Lafayette) and casting off the most odious vestiges of aristocracy. Due to Lafayette's own efforts at the helm of the National Guard, violence had subsided in Paris and a relative peace had settled among the populace. “My dear General,” Lafayette wrote to Washington, “I will tell you With the Same Candour that We Have Made an Admirable, and Almost incredible destruction of all abuses, prejudices…that Every thing Not directly Useful to, or Coming from the people Has been levelled—that in the topographical, Moral, political Situation of France We Have Made More changes in ten Month than the Most Sanguine patriot could Have imagined—that our internal troubles and Anarchy are Much Exagerated—and that upon the Whole this Revolution, in which Nothing will be wanting But Energy of Government just as it was in America, Will propagate implant liberty and Make it flourish throughout the world…”

Enclosed with Lafayette's letter were two items, gifted to Washington on behalf of himself and the French people, and in appreciation of Washington’s embodiment of worldwide liberty: Cathala’s drawing of the demolished Bastille, as well as the main key to the prison. For Lafayette, these items signaled his gratitude and indebtedness to his mentor. Both for Washington's leadership, as well as his friendship that began 13 years earlier on the battlefields of America when Lafayette was only 19 years old—and that now informed his own role in charting France’s revolution. At the end of the letter, Lafayette wrote “Give me leave, My dear General, to present you With a picture of the Bastille just as it looked a few days after I Had ordered its demolition, with the Main Kea of that fortress of despotism—it is a tribute Which I owe as A Son to My Adoptive father, as an aid de Camp to My General, as a Missionary of liberty to its patriarch" (3).

For the delivery of the drawing and key, Lafayette entrusted them to Thomas Paine, who gave them to South Carolinian John Rutledge, Jr., who was then returning to America. Four months later, in August 1790, they were presented to Washington in New York during his first term as President. Upon receiving them, Washington enthusiastically declared them in his reply to Lafayette as tokens of "victory by Liberty over Despotism” (4). He would prize them for the rest of his life, displaying them at his Presidential homes in New York and Philadelphia during the entirety of his time in office. At the end of his two terms, he had them sent to his home, Mount Vernon, where he had them prominently showcased in the entrance hall of his residence for all to see, “a mark of his appreciation to his French pupil and a recognition of their symbolic importance in America” (5). They would remain on display at Mount Vernon for the rest of his life—the key enclosed in a glass case with the framed drawing hung below—and then through three generations of Washington’s family who resided there.

Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, and George Washington first met in Philadelphia on the night of July 31, 1777. It was a critical and dire moment for the fledgling American army, then reeling from the loss of Fort Ticonderoga, and anticipating the British Army's imminent invasion of the Philadelphia. Despite the differences in their backgrounds, as well as their physical and emotional demeanor, the 19-year-old Lafayette and 45-year-old General Washington both shared a similar lust for military glory. Lafayette, an orphan and wealthy aristocrat, had married into one of France's most prominent families with close ties to the family and court of King Louis XVI. Not suited to Versailles's court life, and with his military commission terminated following reforms to the French military, Lafayette is said to have become inspired by the cause of American liberty after dining with English King George III’s brother, the Duke of Gloucester, who supported the rebelling Americans. "When I first learned of that quarrel, my heart was enlisted, and I thought only of joining my colors to those of the revolutionaries," Lafayette later wrote (6).

Seeking the military honor denied him in France, in early 1777 Lafayette attained a commission as Major General in the Continental Army from American agent in France, Silas Deane. Defying orders from the French King forbidding French soldiers from fighting in America, Lafayette purchased his own ship, La Victoire, and sailed for the United States. After weeks at sea he arrived in Charleston that summer, and then made a grueling overland journey north to Philadelphia. Upon his arrival, he was initially spurned by the Continental Congress, who had grown frustrated with the numerous foreign adventurers who came to America with high commissions, but who often offered little in return. Due to his wealth and noble connections, Lafayette was reassessed as a crucial means for attaining much-needed French support and was attached to General Washington's command. Unlike previous foreign volunteers that Washington had begun to loathe, Lafayette quickly showed himself to be an adept and skilled leader, both on and off the battlefield.

Lafayette's idealism, his ebullient personality, and his willingness to learn, quickly won the affection of General Washington, who brought him into his inner circle and treated him as something akin to a son. Whether seeing in the young Frenchman a reflection of his younger self or expressing "some suppressed craving for paternal intimacy" (7), Washington began to treat Lafayette as his protégé, and they became trusted friends and confidants. As Washington later wrote to Gouverneur Morris, “I do most devoutly wish that we had not a single Foreigner among us, except the Marquis de Lafayette, who acts upon very different principles than those which govern the rest” (8).

Through the years he fought for America, Lafayette continually proved his commitment to the cause of American liberty, and in the process became beloved among his fellow soldiers and the American public alike. This was shown at the Battle of Brandywine Creek—his first battlefield action—where he bravely coordinated retreating troops, getting wounded in the process; at the Battle of Gloucester, his first battlefield command; through the harsh winter at Valley Forge, where he supplied clothing and supplies for his fellow soldiers, purchased at his own expense; at the Battles of Barren Hill and Monmouth, where he showed courage and tactical proficiency; in Rhode Island, where he acted as an intermediary between the American and French armies; and finally, in the southern theater of war and at the siege of Yorktown, where his command of troops was instrumental in Lord Cornwallis's surrender that secured American independence. Through all of this, Lafayette remained devoted to Washington, even as many in the army and in Congress questioned Washington's leadership. “I am," Lafayette wrote to Washington during the Conway Cabal, "now fixed to your fate and I shall follow it and sustain it as well by my sword as by all means in my powers" (9). This was crucially felt in Lafayette’s successful lobbying of King Louis XVI to provide more French military support to the American army, without which the war would not have been won. In response to his unwavering commitment to the American cause, Washington wrote to Congress that Lafayette "has been, upon all occasions, an essential friend to America" (10).

Following the war, Lafayette returned to France a hero and a celebrity, where he became known as the "Friend of Washington", and later, the "Hero of Two Worlds". Like many foreign volunteers who fought for America, Lafayette brought back to his home country burnished republican ideals—and for him, the goal of changing French society. During the period anticipating the French Revolution, he became a fixture in Paris's elite salons, where Enlightenment ideas fermented, and the American Revolution provided an example for societal change. A leading voice that agitated for civil and economic reform, Lafayette became an outspoken proponent of democracy, and led efforts for religious freedom and the abolishment of the slave trade. An ardent supporter of continued French-American relations, he lobbied for increased trade and commerce between the two countries, and through his unofficial diplomacy, acted as an intermediary between the United States, France, and other nations.

In 1787, during the fiscal crisis that precipitated the French Revolution (partly a result of French support for America), he was selected to sit on the Assembly of Notables, where he called for the reinstatement of the Estates General, and further called for the formation of a national representative assembly—a radical proposition at that time. When the Estates General was convened in May 1789, Lafayette was elected to the Second Estate of Nobles. That June, French society was reeling from rising food prices and increasing civil discord. By mid-June, the Third Estate declared itself the National Assembly and in the Tennis Court Oath of June 20 vowed to create France's first constitution. On July 10, Lafayette submitted to the Assembly his Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, penned with the assistance of Thomas Jefferson, and whose opening language echoed America's own Declaration of Independence, stating that “Nature made men free and equal." Four days later the Bastille fell and catapulted Lafayette to the forefront of the Revolution.

In October 1824, thirty-five years after gifting the Bastille relics to Washington, and twenty-five years after Washington's death, Lafayette was reunited with them when he visited Mount Vernon during his triumphal tour of America. He was 67 years old, and this was his fourth and final visit to America. As a legendary figure in America’s founding, Lafayette was celebrated throughout all 24 states, visiting each during his over one-year-long tour. At the end of this journey, President John Quincy Adams defined America's indebtedness to Lafayette, stating, "We shall look upon you always as belonging to us, during the whole of our life, as belonging to our children after us. You are ours by more than patriotic self-devotion with which you flew to the aid of our fathers at the crisis of our fate; ours by that unshaken gratitude for your services which is a precious portion of our inheritance; ours by that tie of love, stronger than death, which has linked your name for endless ages of time with the name of Washington..." (11).

While visiting Mount Vernon during his tour, Lafayette was accompanied by his son, George Washington Lafayette, who was named in honor of his dear friend. Lafayette was the sole prominent Major General from the American Revolution still alive, and the return to Washington’s home, where he visited Washington’s tomb and was reunited with the Bastille relics, provided a moment of reflection on his and Washington’s long friendship, as well as their mutual accomplishments that helped create two nations.

In 1858, John A. Washington III, the last of the Washington family to reside at Mount Vernon, sold the property to the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. He also gifted a dozen objects once owned by Washington, including the key to the Bastille, but not the drawing. The family retained ownership of it for the next 33 years. In 1891, it was sold at auction at Thomas Birch’s Sons, in Philadelphia, as lot 268 in the “The Final Sale of the Relics of George Washington”. It was purchased there by William E. Benjamin, who sometime after sold it to publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst. Following World War II it was acquired by Connecticut resident Alan Carswell, which was then left to his wife, and then to the Shriners Hospital for Children and the Masonic Charity Foundation (12).

Personal effects that belonged to George Washington such as this are exceedingly rare to market, even more so those that were as cherished by him during his lifetime, and that were so prominently displayed in his home, like this drawing. It is a unique and remarkable encapsulation of the historical connection between the United States and France, and more so, a testament to Washington and Lafayette's deep and consequential bond, and their mutual pursuit of liberty that was forged across two worlds and two world-changing revolutions.

It now returns to Philadelphia at an auspicious moment that marks the 200th anniversary of Lafayette's tour of America, and on the eve of the 250th anniversary of America's independence.

Footnotes

1. Louis Gottschalk and Margaret Maddox, Lafayette in the French Revolution, p. 117, Chicago, 1969

2. Lafayette, Memoirs of Gilbert M. Lafayette, p. 104. Geneva, 1835

3. Marquis de Lafayette to George Washington, March 17, 1790. The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 5, 16 January 1790 – 30 June 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig, Mark A. Mastromarino, and Jack D. Warren. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 241–243.

4. Washington to the Marquis de Lafayette, August 11, 1790. The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790, ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996, pp. 233–235.

5. Christine Meadows, Souvenir of the French Revolution, p. 29. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, Annual Report, 1987.

6. Tom Chaffin, Revolutionary Brothers, p. 18, New York, 2019

7. Ron Chernow, Washington, p. 296, New York, 2010

8. Stuart Liebiger, Sons of the Father: George Washington and His Proteges, p. 217. Charlottesville, 2013.

9. Ibid, p. 218

10. The Writings of George Washington, Vol. VII, 31.H, Boston, 1838

11. Harlow Giles Unger, Lafayette, p. xxii, Hoboken, 2002

12. Christine Meadows, Souvenir of the French Revolution, pp. 26-36. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, Annual Report, 1987

This lot is located in Philadelphia.