Albrecht Dürer

(German, 1471-1528)

The Sea Monster, ca. 1498

Sale 2052 - Prints and Multiples

Sep 26, 2024

12:00PM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$15,000 -

20,000

Price Realized

$38,100

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

Albrecht Dürer

(German, 1471-1528)

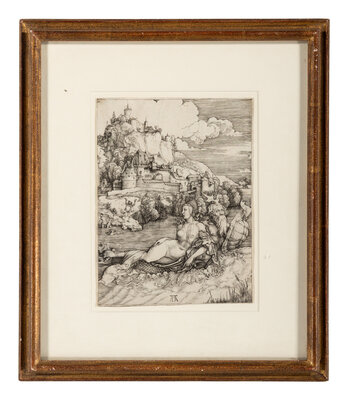

The Sea Monster, ca. 1498

engraving

Sheet: 10 x 7 1/2 inches.

The Estate of Philip Pearlstein

Provenance:

Frederic Robert Halsey, New York, with stamp verso (Lugt 1308)

Sold: Anderson Galleries, New York, The Frederic R. Halsey Collection of Prints, Part VII, March 14, 1917, Lot 114, as The Rape of Amymone

Literature:

Bartsch 71; Meder, Hollstein 66

Lot Note:

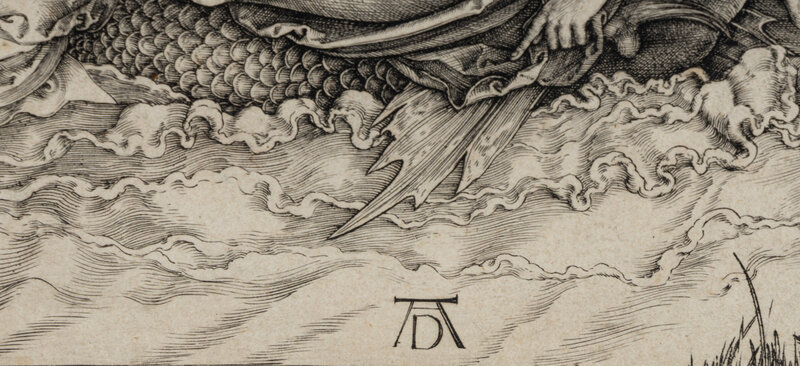

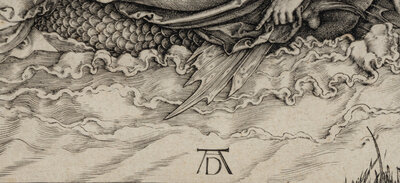

Primarily defined through fine hatched strokes, the delicate rendering of Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) engraving Sea Monster (ca. 1498) belies its bizarre and dramatic scene. Referenced as Das Meerwunder by Dürer, the ‘wonder of the sea,’ it presents a woman, wearing only a contemporary aristocratic headpiece, being whisked away from shore by a bearded merman with antlers protruding from his head and a shield made from a turtle shell, while other women, some also nude, and a man look on in horror.[i] Influenced by classical sculpture and Andrea Mantegna’s Battle of the Sea Gods, Dürer applied his own ingenuity with hybrid creatures to create a compelling scene capable of multiple interpretations, allowing him to advertise his artistic skill in the early days of running his Nuremberg studio. The image would continue to engross future scholars, collectors, and artists, with this impression featuring in the collections of both Frederic Robert Halsey (1847-1918), whose collection helped popularize print collecting in America in the early twentieth century, and artist Philip Pearlstein (1924-2022), known for his oeuvre revitalizing the nude in the 1960s through the twenty first century.

As noted, one starting point of reference for Dürer was Andrea Mantegna’s (1431-1506) well-regarded engraving, Battle of the Sea Gods (before 1481), a monumental fight among aquatic gods, goaded on by the personification of envy, with some bearing fish tails or else riding webbed dragons and horses while splaying tritons, staffs, bones, and, innovatively, a bundle of fish, as weapons of choice. The figures stacked next to each other across the horizontal composition that spans two sheets mirror a frieze from classical Roman sculpture, then heavily of interest to both artists and aristocratic humanist circles.

Dürer, traveling through Italy, copied the right side of the engraving in 1494 (Albertina Museum, Vienna), which includes two nude women carried on the backs of men with fish tails and horse hooves. The preoccupation with antiquity and hybrid creatures, particularly how to create previously unseen monsters out of the natural world, was common among artists of the period, especially as a means to reference their mastery of form and rate themselves among ancient artistic tradition.

Early modern artists, including Dürer, often included hybrids creatures in their works to represent mythological and folk stories as well as Christian tradition such as the torment of St. Anthony. These demons, monsters, and legendary creatures—like chimera and centaurs—were made through synthesis, by combining elements from nature—a deer’s antlers, carefully rendered fish scales and tail, and turtle shell—and applying them inventively into an imaginary form.

As Dürer noted in his postscript to the third book of his The Four Books Human Proportion, “Yet everyone should be cautious not to make something impossible that nature would not allow, unless it would be that one wanted to make a dream work, in which case one may mix together every kind of creature.”[ii] For Dürer, the success of the illusion depended on the expert study of the natural world and its judicial application in order to evoke verisimilitude in his works, including, here, in his sea monster.[iii] However masterful the effect, the composition itself has provoked numerous theories by art historians.

Specifically, art historians have advanced a wide array of possible subject matter for Sea Monster. These have included mythological interpretations from classical antiquity including Venus, the abduction of Amymone and several other abduction stories of sea gods and monsters, German folk tales such as the abduction of Queen Theudelinde, and Erwin Panofsky’s view that it could be “one of those anonymous atrocity stories which, though ultimately of classical origin, were currently reported as having taken place in recent times and in a familiar environment.”[iv]

Moreover, scholar Lorenzo Candelaria notes that, as the large format print was created within a few years of Dürer opening his workshop in Nuremberg in 1495, the subject matter could have been purposefully vague as a means to attract mystery and interest, but, he also points to a contemporary allusion to the work in a chantbook from San Pedro Mártir, Toledo, from around 1500 which places the scene among the labors of Hercules—the rescue of Hesione, the daughter of Trojan king Laomedon, from a sea monster.[v] This possible interpretation of the work by the chantbook illuminator in Spain only a few years after the print’s creation would help to explain the Ottoman attire of the man on the beach—turban, long beard, curved sword—if meant to portray the king from Asia Minor and his aristocratic daughter as though placing the action in Dürer’s contemporary Nuremberg, before Hercules arrived on the scene. In any case, the print, with the kidnapped woman helpfully pausing in the midst of her distress to point with her left hand towards Dürer’s initials at the bottom of the sheet, was undoubtably successful as a showpiece meant to advertise Dürer’s expertise, with this impression in particular influencing two noted New York collectors, Frederic Robert Halsey and Philip Pearlstein.

Frederic Robert Halsey was a major collector of prints, including this impression of Sea Monster, which bears his collector’s stamp verso. Between 1916 and 1919, Anderson Galleries in New York sold Halsey’s collection. It was the largest sale of a print-dedicated collection at the time and helped spark popularity of print collecting in America thereafter. Sold in 1917, this impression would later be owned by artist Philip Pearlstein and is offered by his estate here. The acclaimed artist, like Dürer captivated by antiquity and seriously engaged in the depiction of the human body and the nude, was a fitting collector of this fanciful scene.

Bibliography:

Candelaria, Lorenzo. “Hercules and Albrecht Dürer’s Das Meerwunder in a Chantbook from Renaissance Spain.” Renaissance Quarterly 58, No. 1 (Spring 2005): 1-44

Parshall, Peter. “Graphic Knowledge: Albrecht Dürer and the Imagination.” The Art Bulletin 95: (2013): 393-410.

--

[i] Dürer only referenced this work once in his writings, noting that a Meerwunder was sold on November 24, 1520 in Antwerp. See: Lorenzo Candelaria, “Hercules and Albrecht Dürer’s Das Meerwunder in a Chantbook from Renaissance Spain,” Renaissance Quarterly 58, No. 1 (Spring 2005): 4.

[ii] Peter Parshall, “Graphic Knowledge: Albrecht Dürer and the Imagination,” The Art Bulletin 95: (2013): 395.

[iii] Ibid., 403.

[iv] Candelaria, “Hercules and Albrecht Dürer’s Das Meerwunder,” 24-28.

[v] Ibid., 28-29.

Condition Report

Auction Specialist