Condition Report

Contact Information

Lot 22

Lot Description

Alexander Hamilton Writes To a Family Friend in Puerto Rico, the Countess of Caradeux, Sympathizing with the Perilous Condition of Haiti as Napoleon's Control of the Island Deteriorates

"the disappointment to your views in that quarter contributes to render us extremely sensible to the disasters of that Colony. When will this disagreeable business end? But when would our interrogations finish, if we should attempt to unravel the very intricate and extraordinary plots in which the affairs of the whole world are embroiled at the present inexplicable conjuncture?"

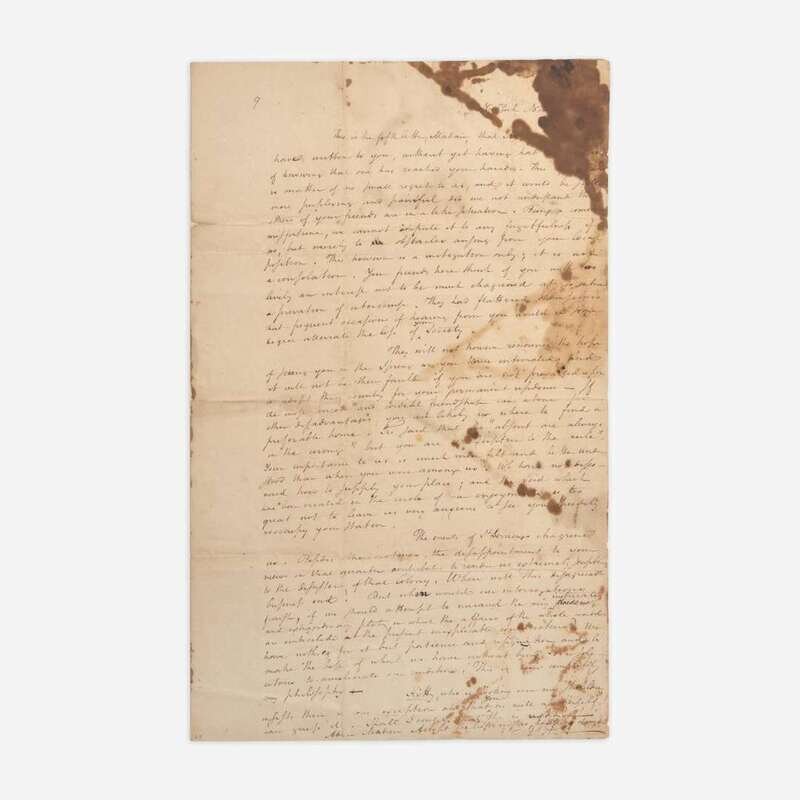

New York: Nov(ember), (likely 1802). One sheet folded to make four pages, 12 11/16 x 7 13/16 in. (322 x 198 mm). Warm autograph letter signed with initials by Alexander Hamilton, to Marie-Jeanne Ledoux Caradeux de La Caye, Countess of Caradeux, sympathizing with her plight while she lives isolated in Puerto Rico after the revolution in her homeland of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Creasing from contemporary folds; many folds repaired; several words affected by ink stain, top right.

New York Nov (obscured by ink)

This is the fifth letter, Madam, that Mrs. H (and myself) have written to you, without yet having had (the satisfaction) of knowing that one has reached your hands. This (circumstance) is matter of no small regret to us, and it would be still more perplexing and painful did we not understand that others of your friends are in a like situation. Being a common misfortune, we cannot impute it to any forgetfulness of us, but merely to obstacles arising from your local position. This however is a mitigation only; it is not a consolation. Your friends here think of you with too lively an interest not to be much chagrined at so entire a privation of intercourse. They had flattered themselves that frequent occasions of hearing from you would in some degree alleviate the loss of your Society.

They will not however renounce the hope of seeing you in the Spring as you have intimated; and it will not be their fault if you are not prevailed upon to adopt this country for your permanent residence--If the most sincere and cordial friendship can atone for other disadvantages, you are likely no where to find a preferable home. Tis said that the ‘absent are always in the wrong’ but you are an ‘exception to the rule.’ Your importance to us is much more felt and better understood than when you were among us. We have not discovered how to supply your place; and the void which has been created in the circle of our enjoyments is too great not to leave us very anxious to see you speedily reoccupy your station.

The events of St Domingo chagrine us. Besides other motives, the disappointment to your views in that quarter contributes to render us extremely sensible to the disasters of that Colony. When will this disagreeable business end? But when would our interrogations finish, if we should attempt to unravel the very intricate and extraordinary plots in which the affairs of the whole world are embroiled at the present inexplicable conjuncture? We have nothing for it but patience and resignation, and to make the best of what we have without being over solicitous to ameliorate our conditions. This is now completely my philosophy--

Kitty*, who is looking over my shoulder, insists there is one exception and that you as well as herself can guess it. Shall I confess that she is right?

Adieu Madam Accept the best wishes of Mrs. H & myself

AH

Alexander Hamilton pens an intimate letter to the Countess of Caradeux, a family friend living in Puerto Rico, sympathizing with her as she was then isolated from her New York friends after a divorce from her husband, a wealthy planter from Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Hamilton comments about the revolution that has ripped apart Saint-Domingue, and offers a rare personal view on the matter. He continues in the hope to see the Countess the following spring and suggests she move back to New York. In a letter dated March 6, 1803 (likely a response to this very letter) the Countess writes that she "no longer has the hope of seeing my friends of America again as I flattered myself this Spring." She reveals her current precarious situation, “Because I was unable to obtain a divorce from my husband it was impossible for me to be near him and I remain in the same position regarding his creditors...to whom I owe fifteen or sixteen thousand gourdes. If I were to live in the same city I would continually be in fear that they would ask me for the money and thereby making me a victim. I live on those credits at the moment, and they mean more to me now that I know that St Domingo is lost for this generation and that I will have nothing more of my fortune. I consequently resign myself to live ignored in my woods of Puerto Rico, rather than going to arouse the pity of my friends.” (Founders Online, National Archives; published in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 26, 1 May 1802-23 October 1804, Additional Documents 1774–1799, Addenda and Errata, edited by Harold C. Syrett. New York, 1979, pp. 89–92).

The "disagreeable business" on Saint-Domingue referred to by Hamilton was the decade-long conflict that began with a slave uprising in August 1791, was followed by Spanish and British invasions, and a subsequent civil war. At the time of this letter the semi-independent colony was embroiled in devastating violence caused by Napoleon Bonaparte's January 1802 invasion. Bonaparte, who had risen to power in November 1799, hoped to resurrect France’s imperial glory and sought to reassert control over its once lucrative sugar colony. However, by the end of 1800, Black revolutionary leader, general, and former slave Toussaint Louverture (ca. 1743-1803) had emerged as the leader over various political factions after driving out the British, defeating rivals in a civil war, and successfully conquering the neighboring Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (modern Dominican Republic). By 1801 Louverture established Saint-Domingue's de-facto independence from France after the creation of a Central Assembly and the ratification of a new constitution that banned slavery and declared him governor for life. In early 1802 Napoleon sent a 30,000-man force led by his brother-in-law, General Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc, to forcibly take back the colony. By November, Louverture was languishing in a French prison cell after being arrested the previous June, and Saint-Domingue was largely back under Napoleon's control, but it came at a devastating price. Thousands of Napoleon's troops--including Leclerc--were dead from yellow fever and the fierce resistance from Louverture's forces. The following April would see the death of Louverture, but also the rise of a country-wide resistance to Napoleon's army when his plans to restore slavery, as he had done on Guadeloupe and Martinique, became known. By the end of 1803, Napoleon's forces were routed, and on January 1, 1804 Haitian independence was declared. It became the first Black republic in the world and the second independent nation in the Americas, after the United States.

Born in Saint-Domingue in 1752, Marie Jeanne Ledoux Caradeux Le Caye married into one of the French colony’s wealthiest planter families in 1777. Her husband, Comte Laurent Caradeux La Caye (ca. 1752-ca.1804/1822) was the younger brother of General Jean-Baptiste "The Cruel" Caradeux (1742-1810), a powerful and radical politico in the region. The Countess and Laurent owned a sprawling plantation in Western Saint-Domingue until the outbreak of the revolution in the early 1790s. They sold the plantation in 1791, and were forced out of the colony in 1793. They presumably resettled near Charleston, South Carolina, with 50 enslaved people (it is possible that this account mistakes Laurent's movements for his brothers). In the decade following the Haitian Revolution, Charleston, along with Philadelphia and New York, became a haven for refugees from the colony (Jean-Baptiste fled to Charleston in August 1792 and established his Cedar Hill plantation). Throughout the 1790s the Countess traveled frequently between New York, Philadelphia, St. Thomas, and Puerto Rico, and, by 1800, was permanently residing in the latter. Her husband’s movements throughout this period are unclear, but by August 1799 he had returned to Saint-Domingue after Louverture had consolidated power and invited exiled colonists to return to help stabilize and rebuild the country. By the time of this letter the Countess and Laurent had initiated a divorce, for unknown reasons. In 1828 she was living in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, and became a naturalized citizen. One account of her husband’s movements indicates he died in Cuba in 1804, while a will, purported to be his, is dated 1822.

The Countess and the Hamiltons likely met sometime in the middle-to-late 1790s in New York City, when Angelica Church, Hamilton's sister-in-law, and the Countess attended the same high society salons.

We have only been able to locate two other letters between the Countess and the Hamiltons: one dated 1801, from the Countess to Hamilton's wife, Eliza, sympathizing with her concerning the death of her son in a duel, and one dated March 6, 1803 (quoted above).

*“Kitty,” is presumably Catherine Van Rensselaer Schuyler (1781-1857), the youngest child of Philip Schuyler and Catherine Van Rensselaer, and the sister of Elizabeth Schuyler Church (1757-1854), Hamilton’s wife. It is also possibly Catherine Church (1779-1839), the oldest daughter of John B. Church and Angelica Schuyler Church, Hamilton’s sister-in-law.