Provenance:

Douglas Rose Collection.

Plaisant Jozef Nestor, Brussels, acquired 1910-1940; thence by descent.

Christie's, New York, Antiquities, 5-6 December 2001, Lot 300.

Christie's, New York, Antiquities, 8 June 2005, Lot 10.

Timeline Auctions, London, Antiquities, 5 October 2012, Lot 1007.

Joe Lewis, Virginia, 2012-2022.

Acquired by the present owner from the above, 20 September 2022.

(Art Loss Register no. S00966370)

Published:

G. Janes, Shabtis, A Private View, Paris, 2002, p. 30. [mentioned in endnote no. 9]

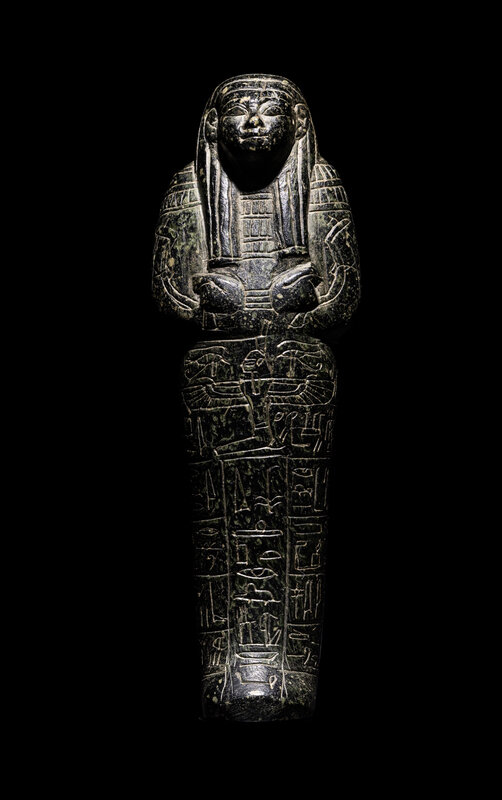

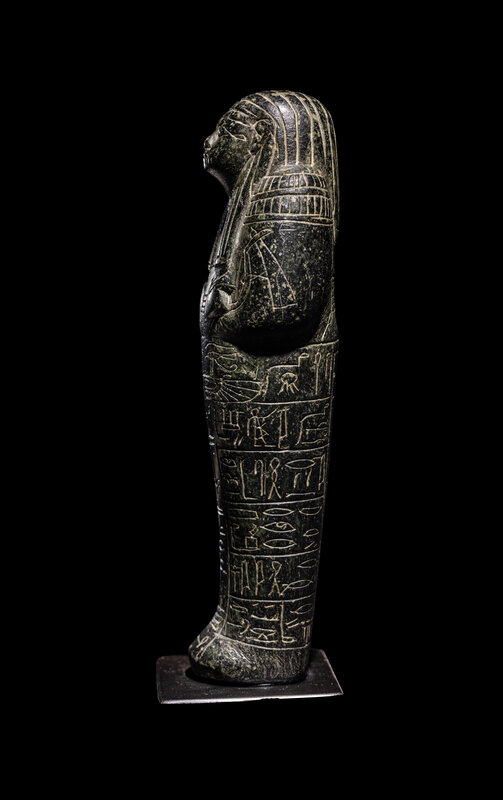

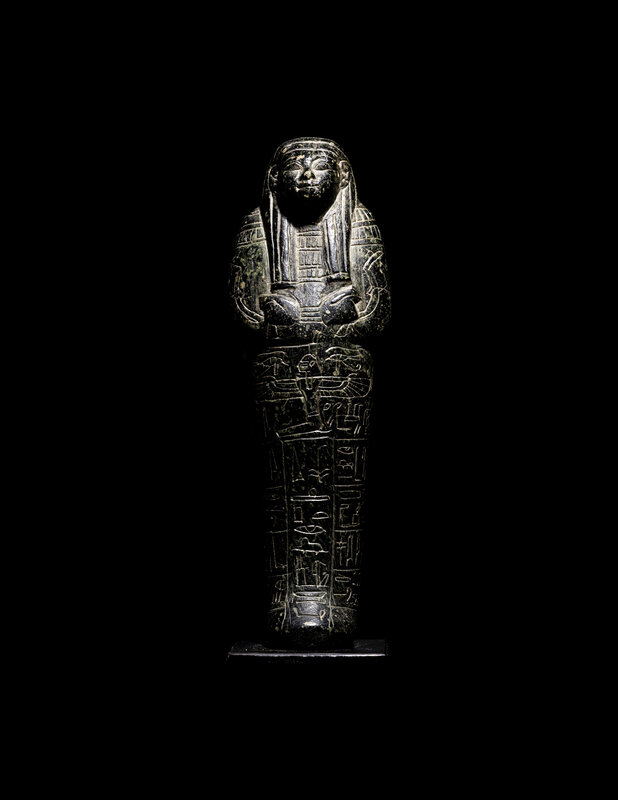

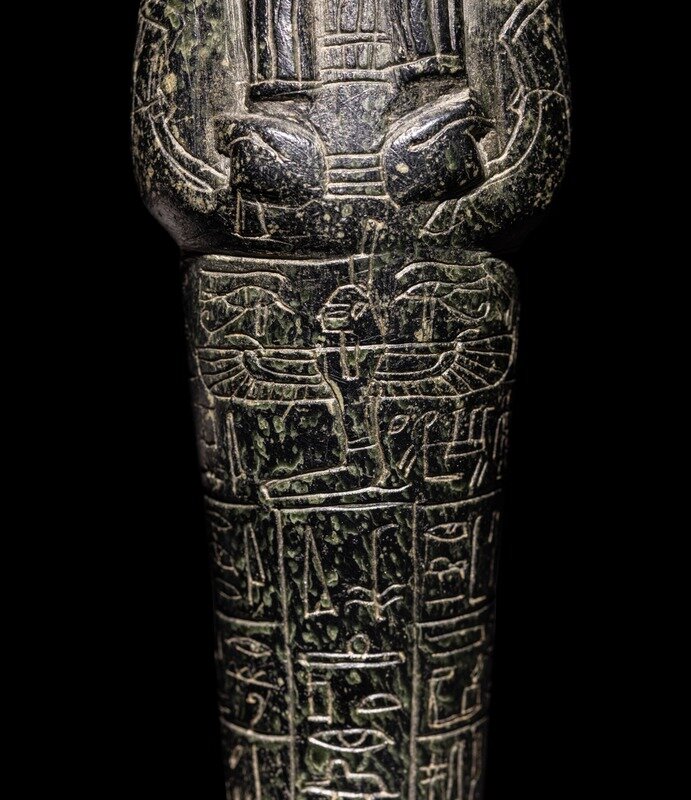

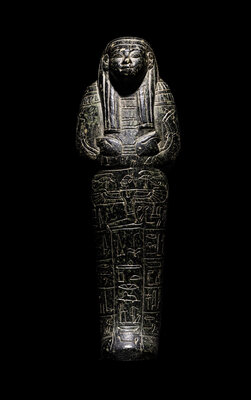

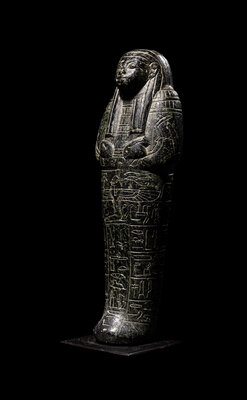

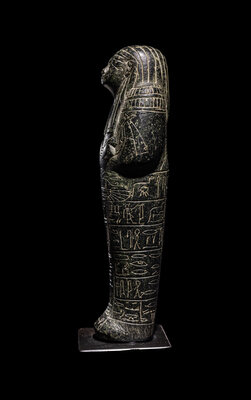

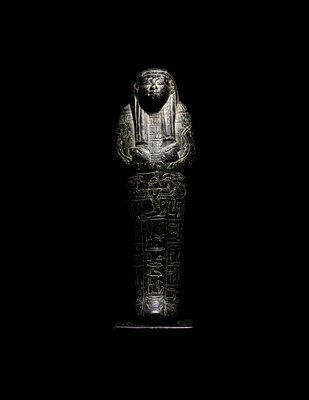

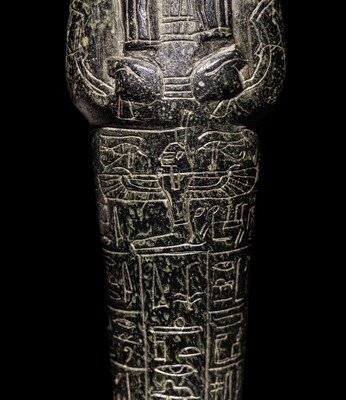

This ushabti exemplifies the advanced craftsmanship of late New Kingdom Egyptian artisans. Despite its initial resemblance to a rigid sarcophagus, the ushabti's careful design reveals subtle serpentine contours, emphasizing the meticulous detailing of the tripartite wig. The confident gaze from its almond-shaped eyes underscores the overall mastery of balance, symmetry, and control.

A near identical ushabti made for Pa-hem-neter, a high priest of Ptah (who held the titles sem-priest and Greatest of Directors of Craftsmen) bears an inscription indicating that it might have been dedicated by the same “May” for whom this ushabti was produced. In that case, he is described as "the illuminated one, the 'Maker of Seals,' May". It is therefore fitting to see such workmanship dedicated to an elite craftsman who spent his earthly days carving, drilling, and finishing ornamental stones.

Produced during a period of Egyptian economic and territorial dominance, this ushabti is a distinctive marker of the era's prosperity. Crafted amidst the logistical challenges of quarrying ornamental stones in the Eastern Desert, the choice of serpentine, a material traditionally used in elite burials, over more common materials like faience or wood highlights May's elite status and his recognition of the capabilities of Memphis funerary workshops.

In terms of function, this ushabti reflects changing religious beliefs during the 19th Dynasty. No longer serving as permanent mummies, these figurines, like May's, were crafted to labor on behalf of the deceased in the afterlife. Depicted with hands holding hoes and a seed bag on the back, the inscribed hieroglyphs ensure the ushabti's response in the afterlife, securing the continuity of agricultural tasks—tilling, irrigation, and sand-moving.