Condition Report

Contact Information

Auction Specialist

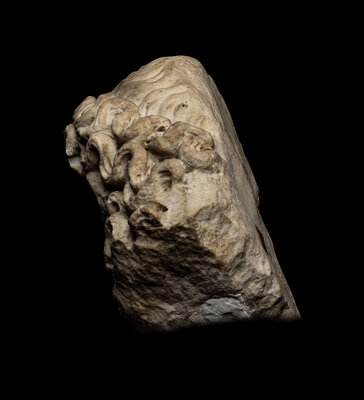

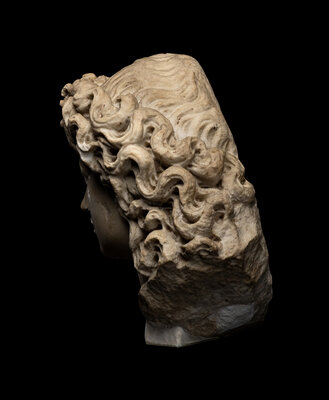

Lot 19

A Roman Marble Head of a Triton

Sale 1273 - Antiquities & Ancient Art: Including Property from the Brummer Collection

Dec 5, 2023

10:00AM CT

Live / Chicago

Own a similar item?

Estimate

$80,000 -

120,000

Price Realized

$226,800

Sold prices are inclusive of Buyer’s Premium

Lot Description

A Roman Marble Head of a Triton

Antonine Period, Circa 2nd Century A.D.

Height 13 inches (33.02 cm).

Property from The Brummer Collection from Drs. John and Pat Laszlo, Atlanta, Georgia